In the annals of scientific progress, certain notions loom large: the brilliant researcher, the groundbreaking discovery, the transformative new application of knowledge.

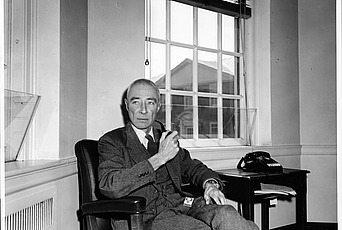

For example, when one thinks of scientific developments during World War II, one will likely picture the Manhattan Project, led by IAS Director (1947–66) J. Robert Oppenheimer, undertaking top secret work at Los Alamos. In developing the world’s first nuclear weapons, Oppenheimer and his colleagues made a truly monumental breakthrough that effectively ended the war, a narrative immortalized by Christopher Nolan’s recent film.

But this is not the only story to be told.

What springs to the mind of Brad Bolman, Member in the School of Historical Studies, when he thinks of World War II is beagles. His research, set to be published as Lab Dog: What Global Science Owes American Beagles by the University of Chicago Press this May, delves into the fascinating and often unsettling story of how the beagle became the most popular dog breed for scientific experimentation in the twentieth century. Although intimately entwined with the Manhattan Project and World War II, this history is far less known.

Through his investigations into beagles, Bolman’s work highlights the value of discoveries that are not always characterized by dramatic triumphs and are instead the result of slow, incremental, but nevertheless meaningful contributions to knowledge.

It also brings into focus the way animals often serve as proxies for human ailments and experiences as scientists address the consequences of human action. Beagles, in particular, have borne the weight of these human dilemmas, serving as both symbols of human empathy and casualties of what we might call “scientific progress.” The entanglement of humans and beagles reflects how our relationships with other creatures shape our understanding of ourselves and the things on which we place value.

A Standard Dog for a Nuclear World

As the world grappled with the devastating power and promise of nuclear weapons during World War II, scientists also began to scrutinize the long-term effects of radiation exposure on the human body. “Quickly, it became clear that the elements and isotopes the Manhattan Project scientists were working with might be quite dangerous,” says Bolman.

In the early part of the twentieth century, the dangers of certain radioactive substances, such as radium, were already well-documented. “Marie Curie’s fatal illness from radium poisoning and the horrifying cases of watch dial painters falling sick from radium paints were common knowledge,” Bolman recounts. But plutonium, a newly discovered and highly unstable element, posed a far greater mystery. How would prolonged exposure to even small amounts of such radioactive materials affect human health over decades?

To investigate such questions, at the same time that Oppenheimer and his team were at work in the desert of New Mexico, so-called “health physicists” elsewhere in the U.S. were conducting basic biological research into the effects of plutonium exposure. Gathering such data with traditional lab animals, like rats, was extremely difficult, so scientists turned to larger animals, including dogs, to gain greater insight.

In their quest, they strove to identify a so-called “standard dog,” a consistent, predictable research subject that could be used across various experiments, a model organism that would allow scientists to draw reliable conclusions about the effects of radiation on living beings. “A lot of different dog breeds were explored,” says Bolman. “But beagles were among the most popular dogs in the United States at the time. With their medium size and gentle temperament, they emerged as the breed of choice.”

Large-scale beagle laboratories were established across the United States. These facilities subjected dogs to controlled doses of radiation. “Beagles were fed radioactive food or injected with small amounts of radioactive material, for instance,” states Bolman.

These experiments served multiple purposes. On one hand, they were meant to help scientists understand how to protect those working directly with radioactive materials. On the other, they addressed broader questions about the safety of nuclear technology. “People started to think very quickly about what would happen when nuclear reactors became widespread after the war,” explains Bolman. “Scientists asked whether it was safe for soldiers to fly in planes powered by atomic reactors, or for employees to work for years at civilian reactors.”

Indeed, research with beagles did prove to be important for establishing the terms of radioactive safety. In 1949, American, British, and Canadian researchers met at Chalk River in Ontario, to decide on international standards for “safe” exposures to radiation. “The conference resulted in strict limits for what scientists called a ‘permissible dose’ of radiation, which would transform operations at nuclear laboratories,” states Bolman. Letters exchanged among scientists working on nuclear projects, which Bolman analyzed for his book, showed that there were concerns over the potential impact on ongoing research. “Scientists, for instance at Los Alamos, were worried that if the Chalk River limits were adopted as the U.S. federal standard, many of their projects would have to be shut down,” continues Bolman.

The first beagle research programs aimed to revise those standards. Starting in 1950, beagle projects were set up at the University of Utah, the University of California Davis, the Hanford Site in Washington, the Lovelace facility in Albuquerque, and the Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago. Research conducted at these facilities became the foundation for future ideas about radiation safety and protection.

Yet despite their critical contributions, the role of beagles in research has remained, for many years, largely overlooked. Studies with dogs, which were once considered essential to scientific progress, became less popular with the public. But Bolman also attributes this lack of attention to the nature of the work itself, which was slow, methodical, and lacked the headline-grabbing breakthroughs often associated with major scientific achievements. Beagle research was defined by smaller, incremental discoveries.

“When the projects were shut down, due in part to Reagan administration funding cuts,” Bolman explains, “many ended without reaching the grand conclusions scientists had hoped for. The ultimate takeaway from some of these projects was ambiguous, even at their end, many decades later.” This lack of definitive or transformative outcomes meant that beagle research, as Bolman puts it, was not “valorized” in the same way as other celebrated scientific advancements.

However, Bolman emphasizes the need to recognize the importance of this kind of research, even if it did not produce groundbreaking discoveries. “This sort of quotidian, basic work—like taking care of a dog for decades—is really critical to the production of knowledge,” he argues. “Although not all research projects ultimately produce world-changing transformations, they nevertheless contribute to the broader undertaking of trying to understand what human beings are and how we should live—as well as what other animals are and how they should live. This less ‘glamorous’ research is still an essential piece of the history of science.”

“Atomic beagles,” in their silent (or barking) service, have contributed to more than just an understanding of radiation exposure. Their sacrifice is a reminder of the quiet, often invisible labor that underpins scientific progress—and of the ethical and existential questions that arise from a reliance on animals in the pursuit of human understanding.

Blurred Lines for Man's Best Friend

Bolman’s research also uncovers a paradoxical relationship between the scientists and the beagles they studied. Despite conducting sometimes painful experiments, researchers also identified deeply with the animals, even building a sense of community around them. “The people running these facilities thought of themselves as part of a ‘Beagle Club,’” Bolman notes. Club members met regularly, shared “beagle news,” and referred to each other using canine metaphors.

For example, at the Davis laboratory, one of the longest-running beagle research facilities, director Leo Bustad affectionately referred to his colleagues as “Beaglers,” a term traditionally used for those who hunt with beagles. His letterhead featured a cartoon of him with a beagle rummaging through a trash can, and annual reports often featured beagles on their covers. The scientists seemed to define themselves through their relationship with the dogs.

This odd relationship between man and dog further underscores the symbolic role that beagles played in scientific contexts. Beyond radiation studies, beagles were used in experiments exploring the effects of cigarette smoking, the long-term use of hormonal contraceptives, and even Alzheimer’s disease. Just as they served, in Bolman’s words, as “simulated humans” for understanding the impact of radiation exposure, the dogs also stood in for habitual smokers, women taking birth control, or aging parents.

The duality of the beagle—as both deeply humanized and expendable—highlights the blurred lines between species in scientific research. In some cases, the distinction between beagle and human was neatly erased, with the dogs treated as stand-ins for human physiology and cognition. Yet in others, the boundary was stark and unforgiving: many dogs were ultimately sacrificed to benefit the humans they were meant to represent.

Bolman’s research explores how scientists have thought about this contradiction over many decades: “How do you justify killing an animal that is so similar to us, and how do we decide that one animal is more similar than another? Why would you pick a beagle as opposed to a pig or a goat or a horse? These are surprisingly difficult and fundamental questions.”

The ambiguity of the human/animal relationship extends beyond individual experiments to broader ethical debates about animal research. Bolman argues that animal experimentation is often oversimplified into binaries: good or bad, moral or immoral. But the reality is multifaceted. “Some research dogs lived far longer than their pet counterparts, and some studies contributed unexpectedly to veterinary practice. We can be critical of troubling research without arguing that nothing was learned from decades of work,” he explains.

Indeed, many researchers cared deeply for the animals in their charge. During the 1980s, when many beagle research programs shut down, scientists fought to keep the projects alive. In Bolman’s view, they did this not only because of the scientific value of the work, but also because they had grown emotionally invested in the dogs.

Furthermore, some scientists referred to the beagles as the “governors” of the research projects, acknowledging that the daily rhythms of laboratory life were dictated by the dogs’ needs and behaviors. Even the breeding cycles of the beagles shaped the pace of the experiments.

Yet despite the scientists’ emotional attachments and their evident awareness of the dogs’ agency, beagles remained tools for solving human problems. Bolman emphasizes this by saying: “We created the atomic bomb and all of the problems that followed from that, and the dogs emerged, in part, as a way to find answers.” In this sense, the beagles were transformed into “living tools,” proxies used to address the consequences of human action. “It’s our human follies that often become the subject of research with animals,” Bolman adds. “One newspaper story from the 1950s about the beagle research described it as an inability to put a leash on ourselves.” In his book, Bolman argues that if we want to rethink how animals are treated in scientific research, we must first reconsider the organization of human worlds. The problems that humans create—whether nuclear fallout, pharmaceutical dependency, or environmental degradation—so often become the justification for animal experimentation. The story of beagles in science is a record of many of the major dilemmas of modern life.

Bolman, who lives with a rescue dog, stresses that humans have long used dogs as tools in one form or another. “Beagles were originally designed, or bred, as hunting technologies, and many pet breeds were advertised as leisure technologies,” he notes. But other ways of living together, in which dogs and humans can both thrive, are possible. “Doing better for dogs will require us to do better for each other,” Bolman concludes.

Moving Forward to Fungi

Bolman’s next book, focused on the history of the study of mycology, flips the questions that initiated his work on Lab Dog on their head. “With the dogs project, I was interested in what happens when someone conducts research on an organism that is understood to be like us,” he explains. “But in the history of mycology, you see people working to understand organisms that seem radically different from them. We don’t identify so much with fungi: they can be difficult to see and difficult to visualize. I want to explore how scientists deal with this.”

His projects represent two sides of the same coin, seeking to understand how human relationships with both the familiar (in the case of the beagles) and the alien (in the case of the fungi) shape our understanding of ourselves.

Brad Bolman is a Member in the School of Historical Studies. He received his Ph.D. in the history of science from Harvard University in 2021 and moved to the Institute in 2023 after completing postdoctoral research at the University of Chicago’s Institute on the Formation of Knowledge. He is an incoming Assistant Professor in History and Environmental Studies at Tulane University. His articles have been published in the Journal of the History of Biology, Isis, and popular magazines such as The Drift.